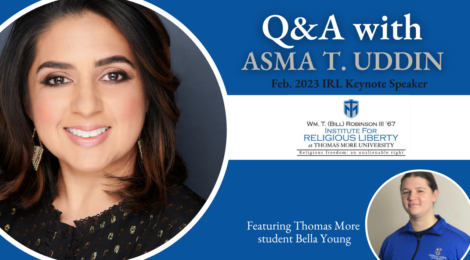

Q&A with IRL Keynote Asma T. Uddin

Thomas More University communications student Bella Young interviews upcoming Institute for Religious Liberty (IRL) keynote speaker Asma T. Uddin. Uddin is a religious liberty lawyer and scholar who served as counsel for the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty and as a fellow with the Aspen Institute’s Religion & Society program. She is currently the visiting assistant professor of law at the Catholic University of America.

Uddin is set to speak at the next Thomas More University IRL event, taking place on Thursday, February 16, 2023 at 7 p.m. in Mary, Seat of Wisdom Chapel.

View the below video and transcript of this interview.

Bella Young: I am here today with the next keynote speaker for the Institute on Religious Liberty’s event. I’m here with Asma Uddin. Would you like to introduce yourself a little bit?

Asma Uddin: Yes, my name is Asma Uddin, and I’m a visiting assistant professor of law at the Catholic University of America.

BY: Perfect, so can you tell us a little bit about how you became interested in the field of religious liberty?

AU: Sure. So my interest, I think if I trace it back accurately, it might be from the day that I was born, in some ways, because I just had a deep fascination with religion my entire life. My father, well before he had me, was, I say was because he passed away in 2006, a deeply religious man. When he was in ninth grade, he actually set out to memorize the entire Quran, in perfect classical Arabic and succeeded in doing so. And so every morning he would recite a portion of the Quran out loud as a way of keeping his memory fresh on it. And so just being in that environment from a very young age; He was also the person who essentially taught Sunday School in Miami, helped start a lot of these Sunday schools. As a civil engineer designed a number of mosques, and not just in South Florida, but also in different parts of the United States. And so, that was the bigger environment that I grew up in. One that was religious, but religious in a way that was really authentic. One that was about personal spirituality, but also about getting back to the community in very concrete ways. So I had this understanding even as a kid that religion plays a big role in people’s behavior and their desire to do good for the world. So I would start there. And then there is certainly the part where I just love having conversations about it and exploring other people’s experience with religion. So as a middle schooler, I used to carry around a copy of Karen Armstrong’s A History of God and try to use parts of it to generate interfaith conversation with my colleagues. I grew up in my Miami, Florida, so it was a really diverse place. But of course, mostly, at least in schools that I went to mostly Christian. And so that’s the personal. Another part of the personal experience ultimately now that kind of begins to get into the space of religious liberty is also personal stories of my religious community facing backlash. Sometimes, you know, really traumatic incidences of hate crimes, certainly kind of hit home that religion can be great and this wonderful thing, but it can also be a source of contention and division. And finally, I think, you know, that was certainly led me to religion and then as I went to law school, I wanted to find a way to continue to stay in the space of religion, even as a lawyer, so that necessarily is a religious liberty. It’s where religion and law meet. And I’ve stayed interested in it because it’s just, I think, one of the biggest issues in our country and around the world, and there’s always there’s so much to learn.

BY: Yeah, can you tell me a little bit about your work as a religious liberty lawyer?

AU: Sure, so I started in this field in late 2009, is when I made the transition from like my initial couple years after law school, which was in a white-shoe law firms, kind of dealing with a lot of corporate and commercial issues. Definitely not a lot there dealing with religion. I did do some pro bono work, but ultimately, I was drawn to my passion and moved over to a nonprofit law firm that specializes in religious liberty. And I started off doing actually international legal work. So I was traveling to places like Indonesia, and the Middle East, North Africa region. So I was doing trainings in Jakarta, but also in Amman, Jordan, and elsewhere. We made a trip to Morocco. Working with lawyers on the ground essentially, I created something called a legal training institute, with support from the U.S. State Department, to help lawyers on the ground kind of figure out what religious liberty law is and what that entails and like what is sort of the full scope of that protection under, specifically our international human rights treaties like the ICCPR [International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights]. And then actually, in that capacity, bringing cases challenging, for example, blasphemy laws in these countries. So I started off in the international space, which believe it or not, I mean, certainly dealt with really sad scenarios where religion and religious liberty is to be frank, a life or death issue, to then just kind of transitioning over to the American arena, and where our disputes are, certainly back then, were more subtle and nuanced. I think they legally and intellectually, they’re nuanced, but I think the way that they have kind of become mired in politicization in our political tribalism in this country, it’s, in some cases, actually is becoming a little bit closer to life or death issues and some scenarios because there’s just sometimes a lot of violence or hatred that gets mixed up in this. So that’s some of the work I’ve done. And then so once I moved over to the domestic space, I got a chance to work on cases that went to the U.S. Supreme Court, and of course, other cases didn’t make it that far, but sort of like the full variety.

BY: So your experience is obviously expensive on an international scale, on a domestic scale. So your research focuses go beyond religion, encompassing gender and politics as well. How do you see these focuses and these areas converging to enrich scholarship?

AU: Yeah, so the first ways that this converge was concurrent to my kind of switching into the space where I was working on religious liberty as a lawyer. I was also very much interested in the question of gender in Islam specifically. And so I started a web magazine at the time that kind of took off pretty soon after I started it, that kind of explored a wide variety of gender issues with them with some community. And that at that time, gender was not the way it is talked about now. It wasn’t a question of sexual orientation or gender identity instead, it was very much about the male and female divide and the way that, you know, we navigate gender roles in marriage, how quite, you know, even sort of like the courtship process and the Muslim community, the questions of like gender segregation in the mosque, things like that. It was the sort of stuff that I was talking about and exploring with my writers and my readers. And so at the time, one of the topics that a lot of my writers wanted to explore was just the role of a headscarf or in some cases, even the burka and the face covering, and their experiences with any one of those, often the headscarf because in an American Muslim context, there aren’t that many people cover their face, but a lot of people who do wear headscarves so like their struggles with that in a society where that is deeply misunderstood. And also just within a family dynamic like how the headscarf can complicate things, even of course of Muslim courtship, to be frank. So you’re kind of talking about those things, but then also having this foot in international religious liberty space where in addition to Muslim majority states, I was also looking at places like France. I’ve written considerably about places like France, where there are legal restrictions on different types of Muslim religious garb. We even for a while Turkey was in that same space where women wearing a headscarf could not sit for university exams. And so really kind of looking at like, Hey, it’s okay to have these types of conversations about things that are happening in your religious community, among people who are in the community and like just socially like that, you can have those debates, and you can persuade people to take on one or the other position on these things. But it becomes a very different issue when governments get involved and they start imposing a particular version of what they think is the right way to dress. And so that automatically kind of connected my interest in gender issues to religious liberty, I mean, that just became a center of that. And it was just a few years ago that France passed laws banning the burqini, which is a modest swimsuit, it basically looks like a wetsuit, on, you know, French beaches and a couple of the towns there. So this is like a live issue, it continues to come up. And then now of course, like gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, sexual freedom, all of that is at the core of our religious liberty battles in this country. So that early exploration of gender, I think, has helped me, because I just developed I think, I mean, I was running a web magazine, so I was there to kind of navigate like diverse views and different perspectives on these things. And that’s really the space that we’re in now. And there’s just so much contention to so many diversity of perspectives on how to approach an increasingly sort of broad understandings of gender and gender expression.

BY: So you spoke briefly about your readers, could you speak on the inspiration for your most recent book, The Politics of Vulnerability, and how it takes a unique perspective on the Muslim/Christian divide?

AU: Yeah, so I think a lot of those things that I’m kind of referring to like when I talk about sexual orientation, and sexual freedom more broadly, as like, the crux of so many of our religious liberty issues. I think at the same time, being in this space and talking to a lot of the Christian individuals and groups that are bringing challenges in the legal arena against particular requirements that they have helped facilitate, same-sex weddings for example, like that, that is a site where there’s been a lot of cases. We’ve had the Christian baker case, we had, I mean, not the Supreme Court, but there was the Christian florist who didn’t want to make flower arrangements for a same-sex wedding. There was also a photographer that we represented who in that case in New Mexico, where she didn’t go on to photograph a same-sex wedding. She wasn’t concerned about photographing same-sex individuals or other occasions but didn’t want to do something that she thought was helping celebrate the same-sex wedding. And then, of course, a case at the U.S. Supreme Court right now that involves a Christian website designer who doesn’t want to make a website, a wedding website, for same-sex couples. So all of these things are there and you know, it’s one way to kind of look at that and a lot of people see that is just people not being nice. I mean, it is like a lot of the way that Americans think about this is coming from a place of bigotry and hatred and animus. And I think the difference in my perspective, and as you can see in the title of my book, is that I can explore it these lawsuits, a sort of like defense mechanisms at a time when a lot of conservative Christians are feeling vulnerable, or under attack. In a country where there are major changes happening that are just happened very quickly happened on a huge scale. And have created a sense of being under siege. So looking at the vulnerability there, but then also looking at sort of the divide between a lot of these conservative Christians. In the book, I focus on white, conservative Evangelicals, specifically because a lot of the polling data points to that particular group as being the most hostile against American-Muslims. And so I just sort of want to focus on like what’s been scientifically established and go from there. And, you know, what I noticed, and there’s there are actual social science studies proving this, that a lot of this vulnerability sometimes that is caused by something that’s not about Muslims. It’s caused by these major changes in our culture, around sexual freedom, but they ultimately ultimately end up being manifested in sort of a lot of hostility against a range of minority groups, including American-Muslims, who essentially are kind of considered to be like proxies for the political left. And there’s plenty of reasons why people would think that if you just look at some of the campaign tactics for Barack Obama and for Hillary Clinton, and the way that Muslims were kind of used as sort of like a symbol to stand for a particular political side of the debate. And so I kind of look at like how vulnerability is like the source of a lot of these things that we consider to be hatred and bigotry, and like, how can we kind of have a conversation around that vulnerability, not just on behalf of Christians in this country, but also the types of vulnerability that ends up creating for American-Muslims and the types of true incidences of hate and violence that American-Muslims experience and that are sometimes I mean, I would say often, dismissed by a lot of conservative Christians because we’re all just sort of caught up in our own stories of victimization. Um, so a really long way of just kind of answering your question in a more simple way is that I just want to probe beyond the surface. And just look at how this is really a question about humans, doing things that humans do when they feel like they’re under threat. And how can we just sort of shift the conversation to that.

BY: So is that how the Emmy, Peabody nominated docu-series The Secret Life of Muslims came about? Can you talk about that at all and what the goal of that series was?

AU: So The Secret Life of Muslims project, preceded the book, I mean, it started a while ago. I don’t remember the exact start date, because there were conversations about it that happen that years before anything kind of manifested. But no, there is no connection between The Politics of Vulnerability. The Politics of Vulnerability was actually published in 2021 and so that’s quite recent. The Secret Life of Muslims was, yeah, the producers behind it had done another series called The Secret Life of Scientists, where they had had a lot of success, kind of having, making a series of videos that kind of talked about scientists as people, people just want to know more about, like, how do they think and the work that they do. And so they were looking for a new topic, and they were like, what is another group that deeply misunderstood and that has, but obviously a more sort of social political way than scientists, and they kind of landed on Muslims as a community. And now Joshua Seftel, who is behind all of these videos, now he has an Academy Award nominated film as well, that kind of explore some of these things. But I wasn’t involved in that project. And so he kind of set out, he’s like, he used the same format that he used with the scientist project, which is 32 episodes, short episodes, of different people. In this scenario, it was different, all kinds of diverse people from across the American-Muslim community, in an effort to just be like, well, we’re not monolithic. We don’t belong to one race, or one interpretation of Islam, or one set of professional occupations. A lot of people think of Muslims, I think, I don’t know how many exactly, but I think there’s like kind of a conflation of like, Muslims, especially like South Asian Muslims, of being doctors or engineers, but in fact, there are so many different types. Also conceptions are Muslim women, and this idea that somehow they’re oppressed. And so there’s just a whole series again, 32 videos, 32 different individuals who are featured in each of these videos. And they just sort of explore like a wide range of issues related to religion and culture, identity, family, faith. Some really moving ones. I would say a couple of my favorite ones, one of them featured Richard “Mac” McKinney, a former Marine, and he talks about in this video how he actually had plans to blow up the local Islamic center. And he had very detailed plans to do this and there were series of interactions that happened, most prominently with his, his young daughter, when he started kind of lashing out in front of her about Muslims, she kind of looked at him and was just like, and you could tell from the way she looked at it that there was something that fundamentally shifted in their consumption of him when she saw him do that. So he talks about how that actually motivated him to go to the Islamic center and kind of begin to inquire about Islam and they started, you know, answering his questions. And it’s quite remarkable eight weeks after the first meeting actually ended up converting to Islam. And then three years later, he actually became president of that Islamic center. But the first part of the video where you just kind of hear him talking about his plans to essentially go and blow up this place, how he was amassing the weapons and kind of coming up with this plan is really jarring. And something that in my work, I have heard other people talking about that, like I know someone at Biola University, which is an evangelical University, hearing from her students that their dad is amassing weapons to attack like Muslims and Islamic centers. So it’s not something that’s unfortunately, out of rare as we think it is, or should be. Another one is Rais Bhuiyan, who I know personally, and he was somebody who, a couple of days after 9/11, when he was working as a as a clerk at a gas station was actually shot by someone named Mark Stroman and was actually left blind, partially blind in one of his eyes. And that story became a national story and he actually, Rais actually, publicly forgave Mark Stroman. And in the days before Mark Stoman was executed for this crime, he actually asked to speak with Rais and he actually told him him that he loved him, and that he considered him a brother because that act of forgiveness really kind of showed him the possibilities of just humanity. So I think those two videos are probably the ones that really had the biggest impact on me, but it was just kind of amazing to being part of that team and just watching them kind of navigate that space.

BY: Could you explain the work of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and your role within that organization?

AU: Sure, so I recently wrapped up two terms as an expert advisor to the OSCE which stands for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. And they deal with questions of security and human rights protection in their member states. And there’s 57 member states so it’s actually the United States, Europe, and Central Asia. That are sort of the members of this thing called the OSCE and specifically there’s an institution within the OSCE called, ODIHR, which stands for Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. And that group, that institution specifically is the one that’s focuses on human rights issues and, and monitoring human rights abuses. And so they will provide different type of assistance to their member states to help them protect these human rights like in their countries. And so one of the human rights that they help these countries protect is freedom of religion or belief. Or a short version is a U.S. context is religious freedom. And so when I was part of the panel of experts, I was the person the only person in the United States so they have each like one person from a number of different member states, not all 57 are actually represented. There’s only like 15 of us that are on the panel. So I was a person there on behalf of the United States. And my role really was to kind of bring the American religious liberty perspective to a lot of these guidance documents that we were preparing for these different countries. So one of the ones that I was heavily involved in was one that kind of looked at how you a lot of countries are kind of confused about how to protect security and also protect religious liberty because they feel like if they give too much protection, human rights and that’s going to somehow make it harder for them to keep people secure. So kind of just helping them navigate that particular conflict.

BY: Do you have any recommendations for individuals and communities on navigating current religious and/or cultural divides?

AU: My advice is ultimately the one that I explained in detail in my second book, The Politics of Vulnerability, which is ultimately about kind of looking beyond the headlines. Sometimes we kind of just read a news story about a particular conflict and we take it as like absolute truth; that is what it is. Whereas I can tell you as somebody kind of being on the ground and in talking to all the different people involved, a lot of times when I read articles, news articles or opinion pieces, I can see the obvious flaws. So just look beyond the headlines. Don’t believe everything you read on the internet and actually try to reach out to the actual people, the actual humans who are involved and learn their story. I think there’s a lot of focus today on storytelling and an understanding people’s stories and I think that’s exactly right. Just see them for who they are and their actual experiences as opposed to how they’re talking about in the public media.

BY: Awesome. Thank you so much for coming and talking with us today. We really appreciate you taking the time to come and sit down with us.

AU: Great, thank you.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.