Thomas More University (Villa Madonna College) and the “Day Law”

Submitted by Thomas Ward, Thomas More University Archivist | Preface by Judy Crist, Executive Director of Communications and Creative Services

Preface: Black History Month has arrived and the curious among us were interested to know more about the historical context of this institution as a Catholic college dealing with racially motivated laws and segregation (in the earliest years), and how to apply Catholic social teaching as the years have progressed. Archivist Tom Ward did an excellent job pulling together the following information on the journey and progress that one small liberal arts college in Kentucky has made while grappling with these difficult and complex issues.

The Commonwealth of Kentucky was not unlike most other southern states at the turn of the 20th century. It was a time when “Jim Crow” reigned throughout the region as states codified the 1896 Plessy vs. Ferguson Decision of the United States Supreme Court, the one that imposed on the nation the infamous “separate but equal” doctrine that was the foundation of segregation. In education, this meant different schools for White and Black students that were certainly separate, but rarely if ever equal.

In 1904, the Kentucky Legislature passed what became known as the “Day Law”, named for representative Carl Day of Breathitt County who introduced it. It was billed as an act “to prohibit White and Colored persons from attending the same school.” One reason stated for this was to safeguard White children from “contamination” – apparently, the bill’s sponsors feared that contamination could occur even at a distance because the law would not allow separate White and Black branches of the same school to be within 25 miles of each other.

In practice, on the level of higher education, Black students (often referred to as “negro” or “colored” students at the time) would not be able to enroll in most Kentucky colleges or universities. This law was intended primarily to affect Berea College, which had long been Kentucky’s only integrated college. Against Berea’s opposition, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Day Law in 1908 (Berea College vs. Kentucky) so that it was forced to segregate.

Whether Kentucky legislators had become more enlightened regarding race by mid-century is questionable, but they passed an amendment to the Day Law in 1950. The amendment allowed Black students to enroll in White schools if there were courses they needed that were not offered at a Black institution. Since it was not established until 1921, the Diocese of Covington’s Villa Madonna College had to abide by the prohibitive Day Law from its inception, even though it conflicted with Catholic values. This amendment opened a door for Villa Madonna College’s administration to move forward in what they regarded as the right direction, though the way in which the college responded showed that they were not going to be in the forefront of the movement to integrate.

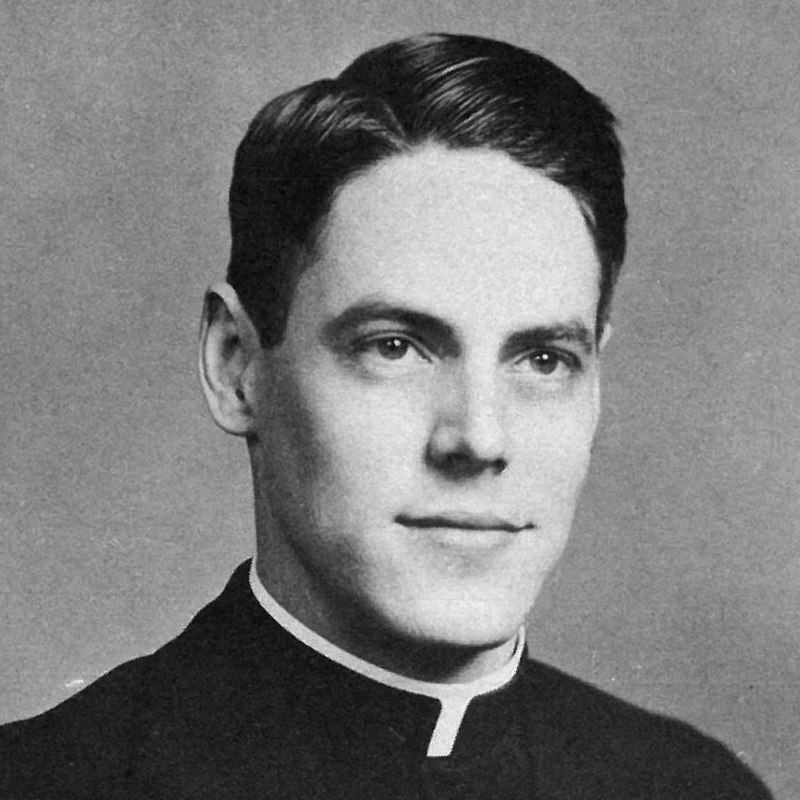

In 1950, Father Joseph Z. Aud was acting dean of the College and Bishop of Covington William T. Mulloy was president. (Bishop Mulloy would later change the titles to president and chancellor respectively). Father Aud reported to the bishop that following the passage of the amendment, he had attended a March meeting in Berea of church-related colleges. As he noted, Father Alfred Horrigan, president of Bellarmine College in Louisville, was of the opinion that “Catholic schools would be legally allowed to accept negro students on the strength of their not being able to take religion and scholastic philosophy at Kentucky State.” (Aud to Mulloy, March 24, 1950) (Kentucky State University was a traditionally Black school in Frankfort).

It was becoming obvious that the Catholic Church in Kentucky wanted to advance the cause of integration. Archbishop John Floersh of Louisville was expected to issue a statement soon and Father Aud expressed his wish that, “I am in hopes that we can see our way clear to admit negro students, and I feel a declaration on that score might indicate that the Church is anxious to take the lead in all such matters.” (Aud to Mulloy, March 24, 1950)

Bishop Mulloy, however, was cautious in his approach. He asked Father Aud to get a copy of Archbishop Floersh’s statement, not that he wanted to give the impression that the archbishop was “going to dominate our diocese, but I do think his statement would be a guide for us… .” (Mulloy to Aud, March 27, 1950) Father Aud complied by inquiring of Father Horrigan what the archbishop would have to say and “whether it is official or unofficial, and how it will apply.” He seemed to think there was no hurry because he doubted that they “will have any immediate inquiries from prospective negro students, and I am not sure what will be done about them if there are.” Apparently, he thought that Bishop Mulloy would make no decisions without knowing first what the Archdiocese of Louisville planned to do, though Father Aud personally wanted “nothing but to accept them if there is the slightest legal possibility.” (Aud to Horrigan, March 28, 1950)

On the question of legality, it seemed that part of Villa Madonna’s concern was whether the state would accept its interpretation of the amendment’s stipulation about the unavailability of certain courses of study at non-Catholic institutions – for instance, would Black students have to register for specific religion or scholastic philosophy courses, or would the more general Catholic content of academic programs allow them to enroll for the benefit of acquiring something they could not get at other institutions? Bishop Mulloy replied to Father Aud, “You know my personal stand on the matter” of allowing Black students to enroll at VMC. “I am by all means for it. However, I think a wise procedure for us would be simply to start without causing any comment at all. I believe in that way we are much more likely to have our attitude accepted.” (Mulloy to Aud, April 6, 1950) The bishop’s meaning was somewhat ambiguous – of whose “comment” was he apprehensive, the state’s or the general public’s, and who would need to “accept” the College’s attitude?

If Bishop Mulloy was mostly concerned about acceptance by the state of the legal position that Catholic schools offered what Black students might not get elsewhere, he was undoubtedly encouraged by a news clipping from the April 19 Louisville Courier-Journal that Father Aud sent him. It noted that three Catholic colleges (Bellarmine, Nazareth and Ursuline) in the Louisville Archdiocese were admitting Black students on the grounds that “the three colleges offer as a part of every course of study a number of semester hours in religion and scholastic philosophy.” All three expressed ‘“satisfaction that the legal barriers against the full application of the principles of Christianity and democracy in the field of higher education in our state have now been removed.” (Louisville Courier-Journal, April 19, 1950, pages 1 and 4) Yet Bishop Mulloy was still reticent about speaking out for the Covington Diocese and hoped that “we will receive something official on this matter, so that we can act accordingly.” (Mulloy to Aud, April 21, 1950) This seems a bit odd because in most other matters, Bishop Mulloy never seemed hesitant to exercise his authority within his diocese.

By the end of the summer, Bishop Mulloy had still not come to a definitive decision on the question of admitting Black students, though it was too late to make a policy that would apply for the fall 1950 semester. In light of an inquiry made by the National Scholarship Service and Fund for Negro Students regarding September 1951, Father Aud pressed the bishop for an answer; if the answer to this particular inquiry was to be in the affirmative, Father Aud wanted to know “if the same decision holds in case there are other direct inquiries from other sources or individuals.” (Aud to Mulloy, August 28, 1950)

By this time, the Catholic colleges of Louisville and Owensboro had issued statements regarding application of the Day Law amendment and Bishop Mulloy requested that Father Aud prepare one for Villa Madonna. He told Father Aud to tell the National Scholarship Service and Fund, “Yes, we will follow the same plan that other Catholic colleges are following.” (Mulloy to Aud, August 30, 1950) Even if he did not take the lead, at least he was now ready to take a stand.

The statement that Father Aud drafted in September justified acceptance of Black students in terms of what seemed strict adherence to the stipulation that “no comparable course of study is offered by a State institution,” while also saying that the decision was “in the full spirit of Christian and democratic principles.” (Draft statement by Aud, September 1950) Yet, even after accepting Father Aud’s statement, the bishop still wanted it delayed until it was nearly time for it to go into effect for fall 1951 because “the least one says about matters of this kind, the less notice is taken of it by the public.” (Mulloy to Aud, September 6, 1950)

It would be interesting to know if Bishop Mulloy was projecting potentially negative reactions onto the general public or more specifically onto the people of his diocese, some of whom may or may not have shared the common prejudices of the time. If the latter were his main concern, it was not unrealistic – even though the Day Law soon became a moot point when the U.S. Supreme Court nullified all such laws with its Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka Decision in 1954. There were many Whites in the south who resisted the dismantling of the “separate but equal” doctrine, but the tide was running against them.

Even before that development, however, the matter was no longer under Father Aud’s jurisdiction because he became a military chaplain in Korea during the war. (He died in 1955 at the young age of 36). His successor was Father John F. Murphy, who was just as eager as Father Aud to make it known that VMC would “take its place along with the other Catholic colleges who have made it clear to all concerned that they stand for Christian principles of interracial justice and equality of education for all regardless of race.” (Murphy to Mulloy, October 20, 1951) Some Black students did indeed enter Villa Madonna College in the 1950s and the numbers increased in the 1960s as racial barriers continued to crumble. During his 20-year presidency, Father Murphy made sure that VMC/TMC always upheld those Christian principles.

*History regarding the Day Law is from “Early History of Black Berea” webpage by Jacqueline Burnside and Wikipedia. Correspondence quoted is in the Thomas More University archives.

______________________________________________________________________________

Trailblazers for Thomas More University

Lois Butler was the first Black student on record to attend Villa Madonna College. She can be found in yearbooks from 1955, 1956, and 1957. There is no record in the 1958 yearbook of her as a senior or graduating in that year or in later years.

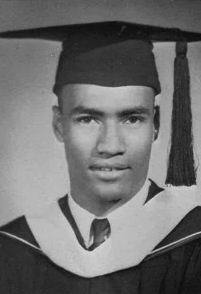

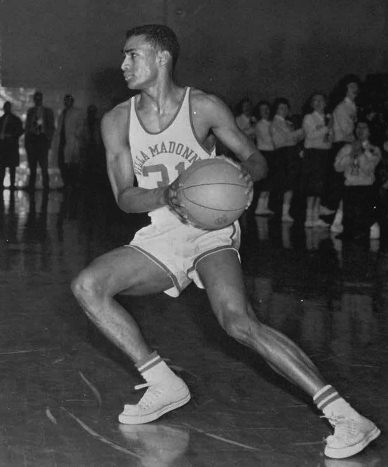

Leslie Stewart ’63 (1941-95) was the first Black student to graduate with a degree, attending VMC from 1959 until 1963. He graduated in general business and was a member of the varsity basketball team all four years.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.